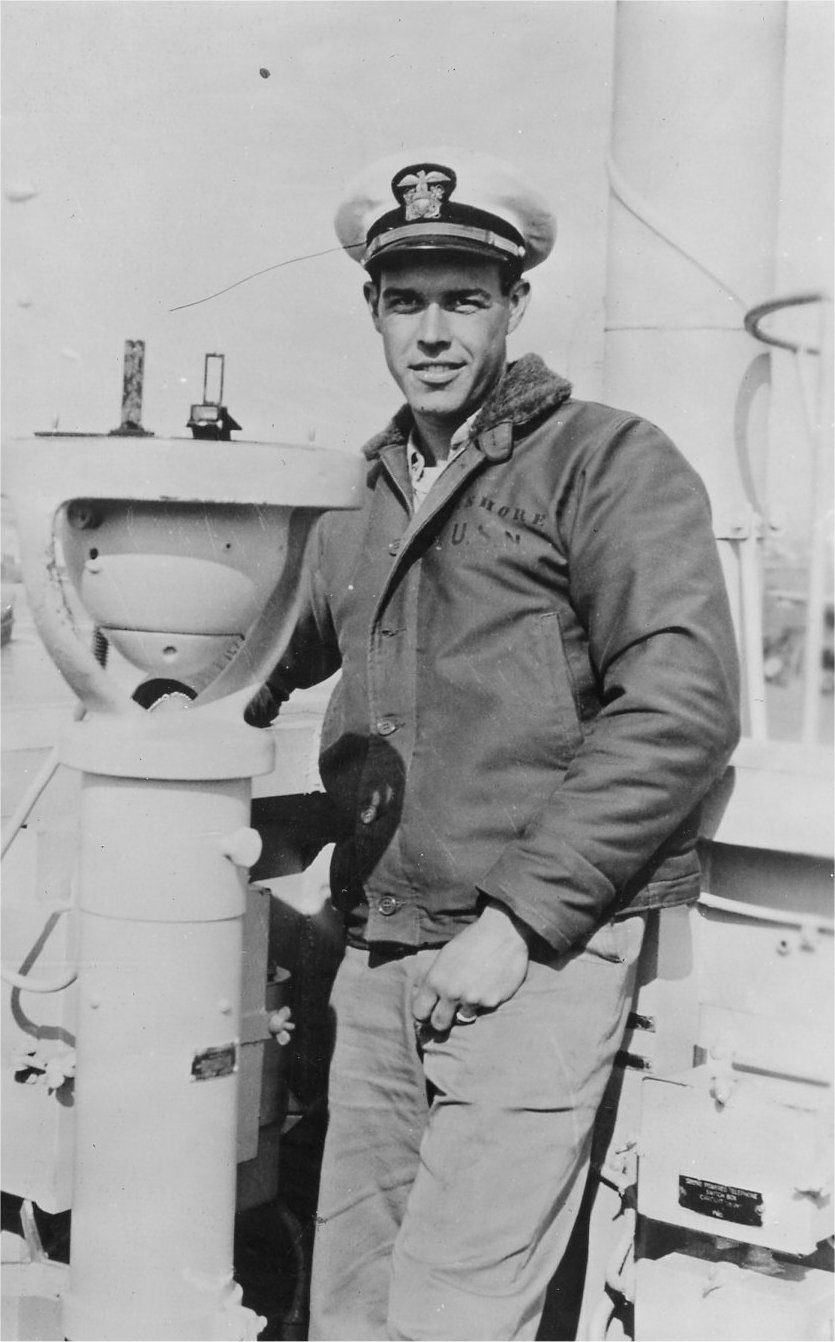

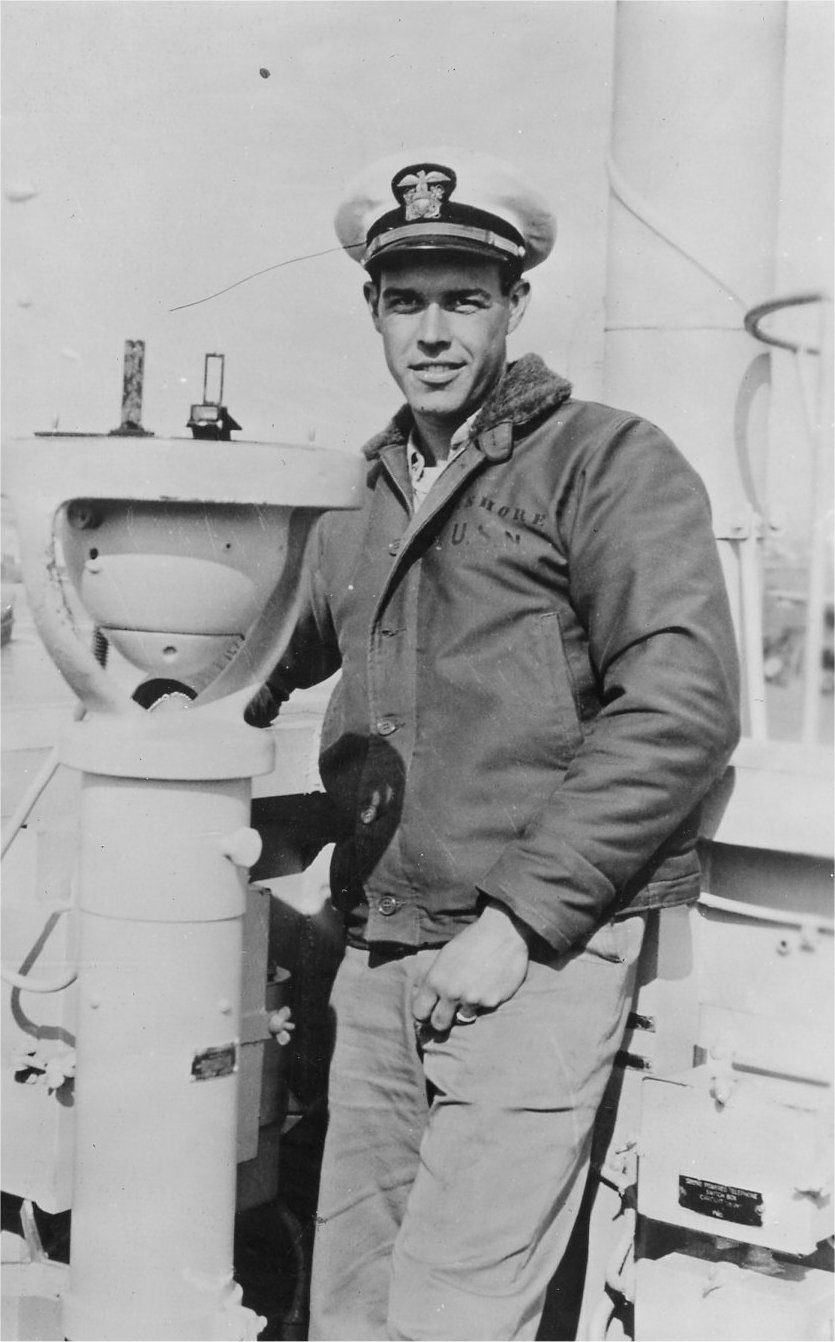

The U. S. Navy "For Better, for Worse" August 1943-Jan. 1946

LTjg. Lee T. Bashore USNR

Contributed by Mel Bashore for his father LTjg. Lee T. Bashore, USNR

The U. S. Navy "For Better, for Worse" August 1943-Jan. 1946

LTjg. Lee T. Bashore USNR

Contributed by Mel Bashore for his father LTjg. Lee T. Bashore, USNR

From Glasgow we proceeded south down the Irish Sea to Falmouth, England thence to Dartmouth and the River Dart (Royal Naval College) for a 5-month period of inactivity while awaiting the LST’s from the African and Italian invasions. During this time we received 3-day leaves for rail trips to London and to Scotland during which I experienced the blackout and London’s nightly bombing raids. German torpedo boats sunk a couple of U.S. landing ships while on maneuvers near Dartmouth in the English Channel and the war began to seem very near. We drew our supplies from the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth and from the U. S. Army Supply Depot at Reading. When LST’s arrived from the African invasions we moved to Portland Bill, to Southampton and finally through the Straits of Dover to London where we encountered the first “Buzz Bomb.” We spent several days at each harbor loading and unloading troops and equipment and making practice runs and landings. After many false rumors of D-Day we loaded British troops and DUKWs (amphibious vehicles) on 2 June 1944 and anchored off Southampton near the Isle of Wight to await the real thing scheduled for 5 June 1944. The weather kept getting worse and under gale conditions we received a 24-hour postponement. Soldiers slept outside on the steel decks in the wind and the rain and ate C-rations. Many were seasick while still at anchor in the harbor. It was a mess! On 5 June 1994 at noon we received a “go” signal and hoisted anchor to form up a convoy of LSTs and escort craft outside the harbor. The escorts were all British since we had been “loaned” to the British command for the invasion. It was actually fortunate for us since they were assigned to Gold Beach between the Canadians on the left and the Americans on the right. The beach was relatively flat—no cliffs to scale. The only obstacles were the steel invasion traps in the water and the gun emplacements on the high ground. We zig-zagged at slow speed all afternoon and evening to arrive off the French coast at 0600 on 6 June 1944—D-Day. En route, two of our sister ships strayed outside the cleared channel and were struck by mines. When they hoisted two black balls we knew they had been hit. We left them behind as we were under orders to stop for no one. Other boats were assigned to rescue and to tow them back to England. As the afternoon wore on we were joined by ships of every description coming from every port and harbor in all of England and Scotland. The Germans could surely see us coming for miles what with our barrage balloons riding high to protect against the possibility of strafing planes. Fortunately not a plane was in sight. At one point we spotted long sections for pontoons such as we had brought from the U.S. and large numbers of old freighters to be sunk to form the artificial harbor for unloading supplies. Although the wind had flattened out for the invasion, it struck again in a few days and totally destroyed the artificial harbor. The invading forces were to be on short supply until the capture of the harbor at Cherbourg several weeks later.

As dawn broke on the invasion beach about 0600, we were looking for our assigned anchorage while shells from the battlewagons roared over our heads and hundreds of allied planes continued to bomb and strafe the beachheads. Bodies of unfortunate soldiers and sailors floated by in the relatively calm sea. From horizon to horizon in every direction were ships of every size and description from all allied countries. Some were large (battleships) and some were so small one would not expect to see them out of their home harbors. The only planes we saw were allied with their freshly painted wing stripes of black and white, which served to identify them.

About 200 yards from shore we cut loose or two small boats and they proceeded ashore with their loads of army personnel. One made it safely while the other became impaled on an underwater obstacle and was sunk. All personnel were rescued or managed to reach the shore on their own.

At 0900 the Beachmaster signaled us to make our landing and we did this in company with countless other LSTs. We were now immovable from the beach until the 21-foot tide ebbed and flowed. Our time there, aside from unloading vehicles and personnel was spent watching for aircraft and watching the columns of German prisoners being loaded onto ships for return to England. While it was relatively calm at Gold Beach we knew that the Americans were catching it at Utah and Omaha Beaches to the west and the Canadians were having trouble to the east. We were listening to radio messages warning of German reinforcements and tanks approaching. It was scary to say the least.

When the tide returned we floated off the shore and were ordered to anchor to await a convoy returning to England after dark. Our captain reasoned that we would be better off on the fringe rather than in the center of a bunch of ships with drifting anchors, etc. We secured general quarters and retired from out battle stations for the first time in some 24 hours. It seemed not over 5 minutes when GQ sounded again and we raced outside to find that we were all alone in enemy waters with our other ships ½ to 1 mile away, blinding white star shells illuminating us brighter than day and a German dive bomber buzzing around overhead waiting for the kill. Finally he was ready and although we could not see him, he could surely see us! The suspense of the long slow dive was the greatest to my life and I was sure that given these conditions he could not miss. He dropped two big ones and the explosions lifted the ship out of the water—but there was no fire and no screams of pain, just silence, dead silence. After a thorough inspection we discovered, to our amazement, that the only damage was in the galley—the cook’s cakes had fallen!

Capt. Dale, in one of his brighter moments, realized that on the fringe we were sitting ducks with no escorts to protect us. Others must have had the same idea for they all started to haul anchor. In fact he decided that the convoy might not form up fast enough to suit him, and instead of “Damn the torpedos, full speed ahead,” or something equally dramatic, he shouted “Let’s get out of here!” In contrast to the highly organized convoy of the previous night we took off only in the general direction of England, each ship guided by the ghostly blue stern light of the ship ahead. Minefields be damned! How we arrive safely off the English coast at daylight I’ll never know—I was only the navigator.

Everything after D-Day was anti-climactic in that we spent 11 months doing ferry duty between various ports in Southern England and various locations in France. The big ships left the area within 2 or 3 days leaving only cargo ships and landing craft to finish the job. In late June while sailing in the Channel I was handed a radiogram from the Red Cross informing me of the unexpected death of my father in St. Louis, Mo. I was devastated and applied immediately to Capt. Dale for emergency leave. Without hesitation he denied the leave stating that our operation was critical and that he could not spare any personnel at this time. Having seen him operate before, I knew his response would depend more on the person asking than on the circumstances at hand. I was unable to play his game of favorites for the sake of favors and this was one of his ways of showing me who was in charge.

To break the monotony we were sent on one excursion up the Seine River to Rouen. In the Seine I saw the remains of an LST which had on its crew H. R. Shawn from Pomona College and Northwestern Midshipman’s School. I heard later that he was O.K. and can only assume that his ship struck a mine while doing what we were doing. The houses and shops along the river front had suffered much damage but people were carrying on with their lives as though nothing had happened. We experienced the phenomenon in which the incoming tide sends an 8-fooit wave up the river for many miles. As I recall, we had to turn around and head into the wave so that we would not lose control and end up on the river bank. Floyd Hicks and I went ashore in one of the villages and had our pictures taken with some of the natives. This was our only opportunity to travel into France beyond the beachhead.

On another occasion we were given a load of ammunition to deliver to Brest in Brittany on the west coast of France. To get there we had to pass near the Channel Islands of Guernsey & Jersey which were still occup8ied by the Germans. Had they wanted to they could have easily lobbed a shell on us and caused quite an explosion by detonating our cargo of ammo. Apparently they were not in a shooting mood that day., After unloading in greater downtown Brest, and while waiting for orders to return to England, Capt. Dale thought it would be nice to stage a gun drill for the benefit of the local citizens who were watching us constantly from the dock. Since I had now been rotated from navigator to gunnery officer I was theoretically in charge of the drill. Part of our procedure was to load a magazine of live ammo on the 20-mm. anti-aircraft guns and simulate firing the weapons with the safety in place. No sooner had I given the command to load the weapons than the gun nearest the bridge began to fire shells into the air all around the harbor. I was yelling “Cease fire, cease fire” and the shells continued to explode. The Frenchmen were scurrying for cover and yelling what I think were expletives in their native tongue. Did you ever try to stop a runaway gun? There’s not much you can do except to jiggle the trigger and the safety and try to remove the magazine. Whatever, it finally stopped and relative peace was restored. How we missed hitting someone in that crowded downtown area, I’ll never know. We found a broken part inside the gun which probably was responsible for the problem and I was left with several reports to file and the task of developing a safer gun drill procedure. This included the use of an unloaded magazine which was used for drill purposes only, not a very brilliant solution but pragmatic to say the least. Before we left the harbor with our tails dragging, figuratively speaking, I managed to make a deal with one of the locals in which I gave up my only pair of winter long-johns which I had never found a use for, in exchange for a pair of hand-carved wooden shoes which in 46 years I have never found a use for. That was a fair trade in my estimation.

V-E Day was celebrated sometime in May of 1945 and it was exciting to see the lights come on again in a country where we had known nothing but blackouts. Some of the ships in the harbor got a little too exuberant and fired off their remaining ammunition in spite of being a little too close for comfort. It was noisy and colorful to say the least. Within the next few days (or as soon as humanly possible) we had returned our infamous barrage balloon to the Limeys to save for the next war and were on our way in a lighted convoy of LST’s with a destination of New York City, U.S.A. Would you believe 7 days at flank speed and we were home—remember the 25 days it took us to cross the Atlantic the other way? The Statue of Liberty was a welcome sight as we passed by in the harbor and there were flags and “Welcome Home, Well Done” signs on every pier. They were mostly for the larger ships such as the Queen Mary that were bringing thousands of troops home.

We were quickly scheduled for overhaul and were told that we would be sent to the Pacific Theater just as soon as they could get us ready. All but a skeleton crew went home on leave. A short vacation at the Gage’s cabin at Lake Gregory with Doris and a lengthy train ride for both of us to New York consumed most of the free time. This was the famous train trip where Doris, fearing starvation, ran ahead to the dining car while I was “freshening up,” stood in line for over 2 hours and returned stuffed to the gills to ask where I had been. I jumped off the train at the next stop and purchased 2 cold, greasy donuts for my breakfast.

No one, it seemed, was in a hurry to repair LST’s and we were in no hurry to get to the Pacific. We were very comfortable at Pier 42 (home of the ocean liners). Doris befriended a stranger in her hotel lobby (at the Commodore Hotel) and was allowed to rent his comfortable apartment for several weeks. Otherwise we would have been looking for a new hotel room every 3rd day. On the few night that I had the duty and had to remain on board ship, Doris would have dinner on the ship and she would take the subway alone back to the apartment. Who would be foolhardy enough to try that today? She was scared even then. Uncle Gene and Aunt Myrtle lived in Scarsdale and invited us up several times for dinner and “bridge.” Cousin Sonny took us night clubbing in Greenwich Village at his expense. We were given the royal treatment. A few ball games and a few Broadway shows later it was August and the wild celebrations of V-J Day were observed from Doris’s apartment windows. Now I needed a few more “points” and I could become a civilian once again. (Points were earned by length of time in the service and overseas duty if I remember correctly.) Our overhaul was terminated and we were sent to Little Creek, VA home port of the 264 and the Floundering Amphibians. As Navy Day was approaching and ships were overrunning the facility at Little Creek, some yeoman at Naval Operations decided to send ships in every direction, mostly to get them out of sight. Our assigned destination was St. Louis, MO via New Orleans and the Mississippi River for 5 days of public viewing. Doris went to New Orleans and ensconced herself in the Jung Hotel while I took the scenic route around the tip of Florida. We met at the Jung—where else? In a few days Doris left for St. Louis to stay with her friends, the Bradshaws. We had a rough time getting the 264 up the Mississippi as the water was low and we were scraping bottom. It took twice as long to go up river as it did to return to New Orleans after Navy Day. We experienced some near misses with some wild tow barges which acted as though they owned the river.